"The evening his master died he worked again well after he ended the day for the other adults, his own wife among them, and sent them back with hunger and tiredness to their cabins. The young ones, his son among them, had been sent out of the fields an hour or so before the adults, to prepare the late supper and, if there was time enough, to play in the few minutes of sun that were left. When he, Moses, finally freed himself of the ancient and brittle harness that connected him to the oldest mule his master owned, all that was left of the sun was a five-inch long memory of red orange laid out in still waves across the horizon between two mountains on the left and one on the right. He had been in the fields for all of fifteen hours. He paused before leaving the fields as evening quiet wrapped itself about him. The mule quivered, wanting home and rest. Moses closed his eyes and bent down and took a pinch of the soil and ate it with no more thought than if it were a spot of cornbread. He worked the dirt around in his mouth and swallowed, leaning his head back and opening his eyes in time to see the strip of sun fade to dark blue and then to nothing. He was the only man in the realm, slave or free, who ate dirt, but while the bondage woman, particularly the pregnant ones, ate it for some incomprehensible need, for that something that ash cakes and apples and fatback did not give their bodies, he ate it not only to discover the strengths and weaknesses of the field, but because the eating of it tied him to the only thing in his small world that meant almost as much as his own life."

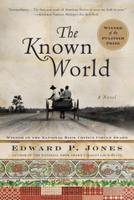

The preceding is the first paragraph of Edward P. Jones' Pulitzer prize-winning novel The Known World. When the book first came out in 2003, I read it and was, frankly just overwhelmed by its scope and depth. I knew it was a great novel but at the same time I knew I hadn't gotten nearly enough out of it. Its huge, sprawling cast and time-jumping narrative had, at least in part, defeated me. I knew I had to read it again.

Last week I finished re-reading the novel, and my suspicions were born out. This is, perhaps, the greatest novel I have ever read. Jones is a masterful writer, but, and this is what I find so remarkable, I have no idea as to how he does it. As that opening paragraph ably demonstrates, his narrative voice is a very simple and direct one. He tells his story plainly and cleanly, in direct, clear sentences, and yet the cumulative effect of this style is one of great power. The reader feels connected to the characters, and their story, in a way that seems counterintuitive with such a, in many ways, dry style.

The story itself should get a lot of the credit to be sure. The germ of the novel lies in the fact that during slavery times in the South there were a number, not a large number but a number all the same, of freed blacks who owned slaves themselves. The novel is about one such imaginary black man in Virginia, Henry Townsend, the man whose death is referred to in the very first line of the novel above. Townsend's death precipitates many a flashback, through which we learn his history, how he came to be freed, how he came to own slaves, all of it. We also learn much about seemingly every person in the imaginary Manchester County Jones sets his story in. The cast of characters is, as I said, large, but each is painted with a sure hand and a keen ear. Throughout the course of the novel, we learn more about all of these characters as the story moves in fits and starts to tell us of both Henry's past and what happens to those his life has touched after his death. It's not a straightforward, point A to point B narrative but rather a weaved tapestry of connected stories. Nonetheless, this is most decisively one cohesive novel, not a loose collection of stories. Every character and every story tie together into one epic piece, in as seamless a way as I can imagine.

Through this large story, Jones also does a fine job of describing the time and place. We learn much about slavery and the relationships among slaves and between them and his masters through the matter-of-fact stories Jones tells. It's an emotional novel, to be sure, and all the more so because Jones steadfastly refuses to grandstand or allow melodrama or pathos to enter his style. That near-dry, putting-the-facts-on-the-table style is consistent throughout, and when dramatic events happen, and they do, they hit all the harder for that restraint.

Suffice it to say I recommend this novel with all my being. As I said, I'm having a hard time making a case for any other to take its place as the greatest I've ever read (sorry Stephen King).

Until Whenever

No comments:

Post a Comment